What Do You Do When No One Takes You Seriously?

The political rookies Andrew Yang and Marianne Williamson will get their shot at Thursday’s Democratic debate, sharing the stage with eight politicians with a combined 150 years of elected experience.

Andrew Yang leaned toward me inside his 2020-campaign headquarters, as he compared federal economic policy to baking muffins. He suggested that his progressive 2020 rivals, like Senators Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren, want to change some ingredients and try again. Yang wants to start from scratch instead.

“The recipe’s not working; this tastes like shit,” Yang said, talking quickly. “Instead of saying, ‘I’m going to make this recipe less shitty,’ it’s like, ‘You know what? Maybe I’m going to bake something else and stop trying to salvage this shit-muffin!’”

He broke out laughing.

“I’ve never used that metaphor,” he explained excitedly. “That’s new!”

Yang, a first-time candidate known mostly for his proposal to give every American a universal basic income of $1,000 a month, is himself new to this whole running-for-president thing. When potential voters watch the first Democratic presidential primary debates next week, arrayed before them will be a former vice president, four U.S. senators, a former governor, a congressman, a mayor, and two people that, polls show, most Americans have never heard of: Yang and Marianne Williamson.

All together, the eight other politicians who will be onstage next Thursday night—to say nothing of the 10 more that will face off the night before—have about 150 years of experience as elected officials. Yang and Williamson have zero. Neither candidate has ever held public office at any level. Each is running the kind of against-the-odds, quixotic campaign that in years past would be easy to dismiss, laugh off, or just plain ignore. But Donald Trump is president, his seemingly out-of-nowhere 2016 victory having served as equal parts apocalypse and inspiration for left-leaning political novices across the country to shoot their shot. And the Democratic Party, four years after its campaign apparatus incited a grassroots revolt by appearing to anoint a favored front-runner as its nominee, is now welcoming all applicants with open arms.

So Yang, a 44-year-old entrepreneur, and Williamson, a 66-year-old best-selling author of spiritual self-help books, will have the same platform in Miami to make their case for the presidency as former Vice President Joe Biden, three-term Senator Bernie Sanders of Vermont, and the rest of the Democratic field. Yang and Williamson share a view that the United States is fundamentally in decline and in need of transformative policies to right itself. Yang sees a mounting economic crisis caused by automation that has already displaced millions of American workers. “These changes are going to get bigger and more disruptive,” he told me. “We’re in the third inning of what experts are calling the fourth industrial revolution—the greatest economic transformation in the history of our country.”

To Williamson, the problems run even deeper. “Our country has devolved,” she told me over coffee recently, “from a democracy to a veiled aristocracy.”

Each of them cleared the deliberately low bar that the Democratic National Committee set for inclusion in the first debates: They secured donations from more than 65,000 individuals across the country, and they reached 1 percent in at least three national or early-state polls.

The criteria elicited concern among party insiders that the debates, spread out over two nights to accommodate 20 contenders, would degenerate into a substance-free circus. The rules also prompted predictable criticism from the candidates who struggled to make the cut, none louder than Montana Governor Steve Bullock, the most prominent Democrat excluded from the first round of debates. Bullock’s campaign accused the DNC of making a “secret rule change” that blocked him from qualifying, and he ran an ad in which a supporter called the decision “horseshit.” Yet when viewed from another perspective, the rules announced in February were refreshingly democratic. Whether by design or not, they created a dynamic in which a traditional political résumé was neither necessary nor sufficient to qualify for the debates. Sitting senators, governors, and congressmen were not guaranteed spots simply by virtue of their position, and it was, as Yang put it to me, “possible for a citizen, through the will of the people” to achieve a measure of parity with the party’s biggest stars.

“It was the greatest coup for us that the DNC put that goal out,” Yang told me.

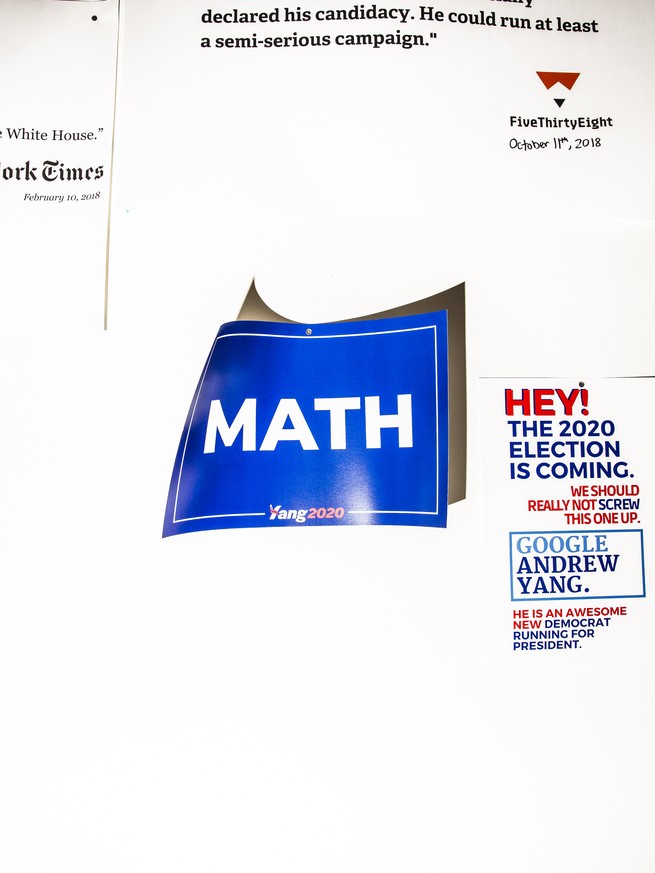

In his sparsely furnished campaign office, just south of Times Square, a handful of young, mostly male campaign staffers were getting ready to jump on a conference call the DNC was holding about the debate rules. On the tables were surplus supplies of the so-called Yang Gang’s counter to Trump’s red MAGA hats: blue baseball caps emblazoned, in all caps, with the word MATH. Situated in this retail hub in the heart of Manhattan, Yang’s headquarters happens to be surrounded by the very businesses—a McDonald’s around the corner, a Starbucks and a Pret a Manger at either end of the block—whose jobs, he said, are most threatened by automation. Yang’s style is unfiltered but not unguarded; he’s funny—and yes, somewhat nerdy—without being vitriolic.

Yang’s campaign, centered on his proposal to provide all American adults with a universal basic income of $12,000 a year until they’re eligible for Medicare, has attracted support from young progressives, a fair amount of libertarians, and despite his disavowals, even some white nationalists. He’s drawn thousands to his rallies across the country and inspired meme-filled Yang Gang anthems on YouTube. Yang blew past the 65,000-donor mark in March and told me he’s already closing in on the 130,000-contributor threshold the DNC set for its debates in the fall. He regularly hits 1 percent—and occasionally a bit higher—in the polls, and while he’s not threatening Biden’s front-runner status, Yang consistently registers in the top half of the crowded Democratic field, ahead of more established names like Senator Kirsten Gillibrand of New York; Julián Castro, the former federal housing secretary; and New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio.

Yang’s website features an eclectic mix of 104 policy proposals, among them Medicare for All; term limits for members of Congress and the Supreme Court; statehood for Puerto Rico and Washington, D.C.; a call for “empowering MMA fighters” and to pay NCAA student athletes; “free marriage counseling for all”; and the elimination of the penny. (He’s also come out against male circumcision.) But the centerpiece—indeed, the entire premise of Yang’s candidacy—is his embrace of a universal basic income, or what he calls the “freedom dividend.” (“It tests well on both sides of the aisle,” he told me of the branding.)

It is Yang’s answer to what he sees as the biggest, and most inevitable, threat facing the American economy, and a large part of the reason that Trump was elected in 2016: automation. The retail sector, call centers, fast-food chains, the trucking industry—all those job engines will be crushed in the coming years by advances in technology, Yang said, necessitating not only a government rescue of displaced workers but a reorientation of the federal safety net. By 2030, he told me, 20 to 30 percent of all jobs could be subject to automation: “No one is talking about it, and we’re getting dragged down this immigrant rabbit hole by Trump.”

The son of Taiwanese immigrants, Yang grew up in upstate New York. He completed degrees in economics and political science at Brown before attending Columbia law school. After a brief stint in corporate law and the failed launch of a celebrity-focused philanthropic company called Stargiving.com, he helped build and then ran a test-prep business that was eventually sold for millions to Kaplan, the industry giant. Yang used the earnings to start Venture for America, a nonprofit that recruits and trains would-be entrepreneurs to launch their own start-ups. There, in the 2010s, he said he realized just how big an economic challenge the country faced, and how unprepared it was to meet it.

“I realized that our work was like pouring water into a bathtub that has a giant hole ripped in the bottom. And the hole was just getting bigger,” he told me. Yang said the loss of 4 million manufacturing jobs in swing states that Trump won—Wisconsin, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Michigan, and Iowa, among others—largely explains his victory. “When Donald Trump became president, I took that as a terrible signal that our society had already progressed to a point where tens of millions of Americans were desperate enough to vote in a narcissist reality-TV star as president.”

Even if voters believe that Yang has correctly diagnosed the nation’s chief problem, it may be a leap for them to see him as the candidate best suited to fix it. Yang told me he decided to run for president after determining that no one else in the Democratic field, including progressive stalwarts like Sanders or Warren, was likely to pick up the banner of universal basic income. “Speaking bluntly,” he told me about his decision, “a lot of the advice I got was that this was a terrible idea.”

Yang told me he was surprised not by the level of support he’s received, but where it’s coming from. “I thought I was going to be the younger, fresher Bernie. But instead I’m something else,” he said. Yang expected to do well among voters closer to his age and perspective, and he has, but even as Democrats have moved steadily left, his push for a universal basic income has met resistance from some of the progressives he thought would embrace it. If his hope was to outflank Sanders and Warren, so far it hasn’t happened.

A selling point of universal basic income is that it’s a simpler, less prescriptive way of assisting people than the complex web of welfare and anti-poverty programs the government presently runs. And by granting it to everyone, regardless of income, Yang hopes to inoculate the idea against expected criticism from conservatives that it’s just an enormous government handout to the undeserving poor. Under Yang’s proposal, people currently receiving food stamps or other welfare benefits would have the choice of receiving cash instead, but they wouldn’t get $1,000 a month on top of the assistance they already receive.

This feature, along with Yang’s insistence that cash go even to the super-wealthy, has generated criticism on the left. “It has a good chance of making low-income people worse off, and it has an especially good chance of wasting significant resources on people who don’t need it,” says Jared Bernstein, a senior fellow at the liberal Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. (Bernstein served for two years as chief economist in Barack Obama’s White House to Biden, one of Yang’s rivals, but he has not endorsed anyone in the 2020 race.)

Yang would pay for his “freedom dividend” with a new value-added tax modeled on those that are common in Europe. But liberals see sales taxes as disproportionately hitting poor people, who spend a higher share of their income on food, clothes, and other necessary living expenses. “We don’t want to hand cash to people with one hand while taking it away with the other,” says Rakeen Mabud, a fellow at the Roosevelt Institute.

Yang insisted his plan would “leave no one worse off.” But his response to criticism about his particulars was simply to say that even universal basic income wasn’t a cure-all. “This policy,” he told me, “is not meant to solve everything for everyone.”

Unlike Yang, Williamson is not running on a single, signature proposal. She has gone further than other candidates in backing reparations for African Americans, calling for the disbursement of $200 billion to $500 billion over 20 years on projects devoted to “economic and educational renewal.” Yet she is a more conventional outsider candidate. One of her ideas, borrowed from the 2004 and 2008 presidential campaigns of former Representative Dennis Kucinich, is for the establishment of a federal Department of Peace.

Williamson told me she saw Trump’s election as a blaring siren that the political establishment had ignored a revolution building underneath its feet. “The American people are not stupid. They know the game is rigged. They know we’re screwed,” she said. “The crying out for change was itself legitimate. Obviously they got the wrong kind of change agent. They got a con artist.”

Williamson, also unlike Yang, has run for office once before: In 2014, she made a bid for the open Los Angeles–area House seat vacated by the longtime Representative Henry Waxman. She finished fourth out of 16 candidates, with 13.2 percent of the vote.

She told me the idea to run for president first came to her—as it did for Yang—shortly after Trump’s 2016 victory, but that it took her a year and a half to “process” it. Her daughter asked, “Why do you need this?” The author of more than a dozen books, including the best sellers Return to Love and Healing the Soul of America, Williamson has been a frequent TV presence as a guest of Oprah Winfrey and Bill Maher.

“I’m not looking to make a fool of myself at this point in my life,” she said. “I’m aware of the inevitable humiliation, the inevitable mockery, the inevitable mean-spiritedness, the inevitable bad pictures.” Williamson has moved to Des Moines to stake her claim on the Iowa caucuses; she stumbled into controversy last week, issuing an apology for calling vaccine mandates “draconian” and “Orwellian.”

Her built-in fan base likely helped position her to make the first debates. But she was closer to the cut-off than Yang was. When we met a few weeks ago, she had just passed both the donor and polling thresholds. “I’m in!” she exclaimed as we sat down.

Whether Yang or Williamson can advance beyond the novelty phase of their candidacy may depend on their performance in the first debates, and whether there’s enough space for two more über-liberal candidates in a Democratic field that has already cut off much of the running room on the left. Their bids are premised, at least in part, on the “anything is possible” notion of the Trump presidency, and the ever-present constituency for nonpolitician, anti-establishment candidates. But neither Yang nor Williamson started out with the advantages Trump had. Neither is a household name, and both lack Trump’s larger-than-life personality.

And for Democratic voters in particular, Trump’s performance in office may serve as a warning against gambling on a political rookie. The question that most stumped Yang and Williamson was not about their analysis of the nation’s problems, or even their proposals for solving them. It was why they, above and beyond their 20-plus rivals for the Democratic nomination, were best equipped to lead the country. Both pivoted back to Trump and their other rivals rather than making an affirmative case for themselves.

Each candidate will get another chance on Thursday night, but answering that question before a national audience may prove to be their biggest challenge.