Trump’s Parting Gift to Joe Biden

Tension within the Republican coalition over the Capitol riot could push GOP-leaning voters into the new president’s camp.

Donald Trump’s chaotic final days in the White House could present President Joe Biden with a historic opportunity to broaden his base of public support and splinter Republican opposition to his agenda.

Recent polls have repeatedly found that about three-fourths or more of GOP voters accept Trump’s disproven charges that Biden stole the 2020 election, a number that has understandably alarmed domestic-terrorism experts. But in the same surveys, between one-fifth and one-fourth of Republican partisans have rejected that perspective. Instead, they’ve expressed unease about their party’s efforts to overturn the results—a campaign that culminated in the January 6 attack on the Capitol by a mob of Trump’s supporters.

Those anxieties about the GOP’s actions, and about Trump’s future role in the party, may create an opening for Biden to dislodge even more Republican-leaning voters, many of whom have drifted away from the party since Trump’s emergence as its leader. If Biden could lastingly attract even a significant fraction of the Republican voters dismayed over the riot, it would constitute a seismic change in the political balance of power.

“There is a universe of Republicans looking to divorce Trump,” John Anzalone, Biden’s chief pollster during the campaign, told me. “They don’t necessarily know how to do it … [but] January 6 was kind of the reckoning.”

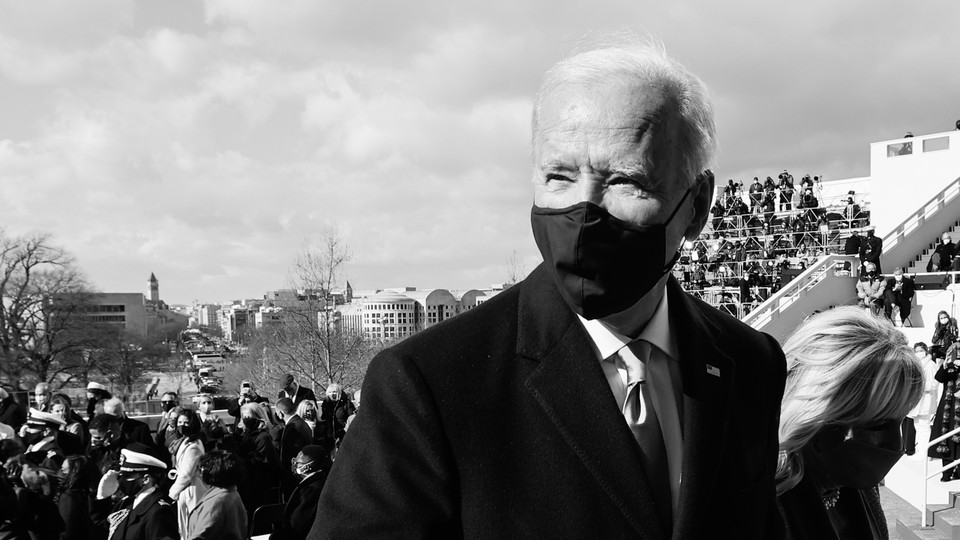

In his inaugural address yesterday, Biden made clear that he will pursue those voters. He centered the speech on a promise to unify the country and made an explicit appeal to voters skeptical of him. But he also unambiguously condemned the threat to democracy that Trump unleashed. In doing so, he defined a new dividing line in American politics, between those who uphold the country’s democratic system and those who would subvert it. “We must end this uncivil war,” Biden insisted.

Beyond providing electoral possibilities for Democrats, the GOP coalition’s widening fissures could provide Biden with leverage to win greater support for his legislative agenda from congressional Republicans, especially in the Senate. Mainstream Republicans’ desire to separate themselves from violent extremists could make some of them more eager to find areas of cooperation with Biden, analysts in both parties have told me. If GOP voters disillusioned with Trump express relatively more approval of Biden, that could also make Republican legislators more comfortable voting with him on some issues. And the bloody backdrop of the Capitol assault could make it more difficult for the GOP to engage in the virtually lockstep resistance that the party employed against Barack Obama during his first months in office.

“If the Republicans play a hard obstructionist role, there is a good chance that they will turn off some of the more moderate Republicans, who will see it as an effort to delegitimize Biden by other means,” the Democratic pollster Geoff Garin told me. “A lot of this will depend not only on how Biden plays his hand, but how Republican leaders play their hand.”

Biden still faces significant headwinds in securing cooperation from Republicans. He can’t threaten many of them politically, because all but three senators and about 10 House members represent jurisdictions that voted for Trump in November. And, as white-collar suburban voters have drifted away from the GOP, most Republican lawmakers have shifted their focus toward promoting massive turnout among Trump’s hard-core base of non-college-educated, nonurban, and evangelical white voters—a group that’s likely to be dubious of any cooperation with the new president.

One measure of Biden’s challenge came when he declared in his speech, “Disagreement must not lead to disunion.” With that warning, Biden became the first president in more than 150 years to use the word disunion in his inaugural address, according to a comprehensive database kept by UC Santa Barbara’s American Presidency Project. No president since Abraham Lincoln in 1861—who spoke when the South had already seceded but the Civil War’s shooting had not yet begun—had thought that the threat of the nation coming apart was material enough to deploy the word in an inaugural address. The only other two presidents who ever did, according to the database, were William Henry Harrison (in 1841) and James Buchanan (whose pro-South maneuvering after his 1857 inaugural helped pave the road to the Civil War). To raise the possibility of disunion, even while cautioning against it, shows how far the nation’s partisan and social chasms have widened after four years of Trump’s relentless division.

Still, the continuing shock waves from the Capitol assault and the ongoing threat of the COVID-19 pandemic may create crosscutting pressures on at least some Republicans to find ways to work with Biden.

The $1.9 trillion coronavirus rescue package that Biden announced last week will offer a crucial early test of each party’s strategy in this fluid environment. The Biden White House’s initial preference is to advance the package through the conventional bill-making process, rather than using a special legislative procedure, known as reconciliation, that allows tax-and-spending proposals to pass with a simple-majority vote, one senior White House official told me this week, speaking on the condition of anonymity to discuss internal strategy.

Debate over whether to employ reconciliation may sound like an obscure process argument, but it has sweeping implications. As the official noted, Biden would have practical reasons to skip the procedure now: It takes longer than conventional legislating (when Biden wants to rush out new money for economic assistance and vaccine distribution), and he may also want to save reconciliation for a larger economic-recovery package he plans to unveil next month. (Usually, reconciliation can be used only once in each budget year, but because it hasn’t yet been employed in the fiscal year that continues through September, Biden theoretically could utilize it twice in 2021 to cover both the rescue and the recovery plans.)

But above all, by attempting to pass the bill the normal way, Biden is making a political statement about his intent to forge compromise between the parties. If the White House and congressional Democrats don’t use the reconciliation tool, they will need 60 votes to break a probable Senate filibuster. That means Biden would need support from at least 10 Senate Republicans, even if he were to pass the measure solely with Democratic votes in the House.

Winning that many Senate Republican votes wouldn’t be easy; winning them without major concessions might be impossible. When Obama took office in 2009 amid the last economic crisis, his initial recovery plan attracted just three GOP votes to break a filibuster. Biden, as vice president, helped negotiate the package with Republicans, who required the administration to cut about $100 billion in proposed spending and enhance tax cuts. To this day, some Democrats believe that those choices slowed the economic recovery during Obama’s first two years and contributed to the GOP’s landslide gains in the 2010 election. (Senator Bernie Sanders of Vermont, who chairs the Senate Budget Committee, may have reflected that lingering frustration when he told ABC yesterday, “If we hear very early on that Republicans do not want to act” on Biden’s plan, “we’re gonna do it alone” through reconciliation.)

The degree to which Biden accepts concessions on his rescue blueprint will set an early template for his administration’s approach to Congress. But the reverse is true too: Republicans’ response to the package will show how many lawmakers feel comfortable fighting Biden from the outset—and how many feel pressure to chart a more nuanced course.

William Hoagland, a former Republican staff director for the Senate Budget Committee, predicts that Biden can ultimately attract 10 Republican senators for his rescue package. Although Hoagland says Biden will likely need to narrow the plan to its core relief elements—for instance, by dropping a proposal to raise the minimum wage—he believes that GOP lawmakers will feel pressure to act. “In the crisis we’re facing, I think [enough] Republicans will come around, and there’s going to be a desire to have some form of showing that, with Trump out of here, we can work together,” Hoagland, now a senior vice president at the Bipartisan Policy Center think tank, told me.

Until the January 6 riot, many Republicans assumed that their party would remain captive to Trump and his base. But Trump’s unending efforts to subvert the election, capped by the attack, scrambled those calculations and weakened his position inside the party. The loss of his Twitter platform—his most fearsome political weapon—further defanged him.

An array of national polls conducted since the attack show that Trump remains extremely popular within the GOP base. But he’s lost voters too. “What you’ve seen over the past two months is this interesting tension, where he’s simultaneously consolidated the core chunk of people who support him while pushing away the marginal people who would put up with [his] antics because they like the policies,” the Republican communications consultant Liam Donovan told me.

In a new CNN survey, for instance, just over three-fourths of Republicans and Republican-leaning independents said they approve of Trump’s performance in office. Nearly as many said they do not consider Biden the legitimate winner of the election. But nearly one-fifth of Republicans and Republican-leaners said they disapprove of Trump’s performance—a much higher share than through most of his presidency—and about one-fourth said they do consider Biden the legitimate winner. Two other telling stats: More than one in four said Trump bears at least some responsibility for the Capitol attack. And roughly the same number also partially blame the congressional Republicans who objected to the Electoral College vote.

Other surveys have similarly captured erosion in Trump’s internal position. About one-fourth of Republicans who approved of Trump in an August survey disapprove of him now, the Pew Research Center found when it recently reinterviewed the poll’s subjects. And a surprisingly large share of Republicans in surveys conducted after the riot by both Pew (40 percent) and ABC/The Washington Post (35 percent) said the GOP should set a different direction or reduce Trump’s influence in the party.

The share of Republican voters who appear open to Biden is smaller, but not insignificant: In the CNN poll, roughly one in five Republican and GOP-leaning voters said they believe he would be, at least, a fairly successful president. About the same number said they view him favorably. Overall, about 60 percent of adults gave Biden positive marks on each question.

Those findings underscore Biden’s potential to expand his audience. For almost all of this century, as the parties have grown more polarized, presidents have only rarely attracted support from as much as 55 percent of Americans. Trump became the only president in the history of the Gallup Poll never to reach even 50 percent approval at any point in his tenure.

Anzalone told me that although he’s not “looking [to set] expectations,” he believes that Biden could begin with a much broader base of support than Trump ever amassed. Given Biden’s strong marks in polls during the transition, he said, the new president has a chance for his job-approval rating “to approach or exceed 60 percent … which is really difficult in this environment.”

In both parties, many operatives are doubtful that Biden could sustain such expansive support for any prolonged period. But even an approval rating consistently over 50 percent might make more Republicans comfortable voting with him—and also improve the Democrats’ odds of avoiding major losses in the next midterm elections, which are typical for a president’s party in his first term.

The key dynamic for the next two years: Biden, a politician with an instinct for outreach, is arriving precisely as Trump’s presidency has left many traditionally Republican-leaning voters unmoored and uncertain. Those disaffected Republicans, Donovan noted, “demographically and otherwise match the sorts of people who have been fleeing the party to begin with. That paints the opportunity [for Biden] there. I think it’s real, and it’s only going to continue absent some other shift [in the GOP] we’ve not seen yet.”

It’s entirely possible that the scale and ambition of the Democratic agenda will unite Republican elected officials and voters alike in opposition, allowing them to bridge their differences over Trump’s legacy and future role in the party. That may even be the most likely outcome of Biden’s first two years. But as Trump leaves Washington stained by the Capitol riot, it’s no longer the guaranteed outcome. The GOP faces the alternative prospect of a bitter fissure between its Trumpist wing and its more traditional faction, which will play out through every legislative choice the party faces, starting immediately with the former president’s Senate impeachment trial. All of that tension and turmoil leaves an opening for Biden big enough to drive an Amtrak train through.