The Continuing Humiliation of Black NFL Coaches

Recent firings highlight a long history of double standards and unrealistic expectations.

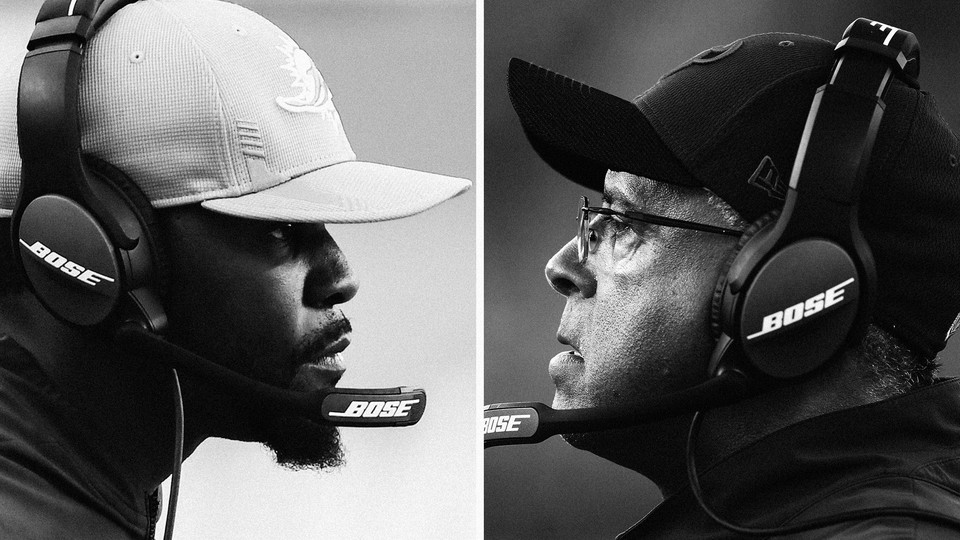

Coaches such as David Culley, just fired from the Houston Texans, and Brian Flores, of the Miami Dolphins until very recently, face a major problem in the NFL. It’s not their pedigree. It’s not their experience. It’s not their ability to relate to players. It’s not their offensive or defensive schemes.

It’s that they’re Black.

That conclusion might seem harsh, but it’s been almost 20 years since the NFL adopted the Rooney Rule, which was intended to give candidates of color a better shot at head-coaching jobs and was eventually expanded to cover front-office openings as well. What the league has to show for its efforts in 2022 is the Pittsburgh Steelers’ Mike Tomlin as the lone Black head coach in the league. The reason is painfully obvious: In a league where roughly 70 percent of players are Black, owners have no real interest in seeing Black coaches thrive.

The league currently has eight head-coaching jobs open, and the names of a bevy of Black coaches have popped up as potential interviewees or even leading candidates. Yet most will be passed over, and the few who get hired are likely to inherit difficult situations—in which they won’t be extended the same patience that their white counterparts enjoy.

This is just how the NFL operates. The firings of Culley and Flores highlight the double standards and unrealistic expectations that Black coaches routinely face.

Last year, the 66-year-old Culley was the only Black head coach to be hired, and now he’s gone after just one season. The Texans’ 4–13 record certainly looks bad, but keep in mind that the team released its three-time Defensive Player of the Year, J. J. Watt, a few weeks into Culley’s coaching tenure. The star quarterback, Deshaun Watson, sat on the bench all season because the Texans were hoping to trade him away. Watson is currently facing 22 civil lawsuits that allege he engaged in inappropriate sexual behavior with a number of female massage providers.

Despite that turmoil, the Texans won the same number of games under Culley this season as they did under his predecessor, Bill O’Brien, last season—and O’Brien had Watson on the field. If anything, Culley outperformed any reasonable expectations based on what he had to work with. Last week, when reporters pressed the Texans’ general manager, Nick Caserio, about why Culley was fired, Caserio had nothing to offer: “It’s not necessarily one specific thing,” he vaguely explained. “In the end, there was some differences about next steps or how we move forward, not necessarily rearview mirror about what has happened.”

The reason Caserio couldn’t provide much insight is because the Texans put Culley in a position where he had no chance to succeed. Culley came in with 27 years of NFL-coaching experience but had never before had a real opportunity to be a head coach. The Texans handed him a thin roster lacking any high-impact players.

Before hiring Culley for the top coaching job, the team also interviewed Josh McCown, a veteran NFL quarterback who has never coached professionally and hasn’t played in the league since 2019. In fact, McCown’s only coaching experience has been at a high school in Charlotte, North Carolina. The Texans are now considering him again, fueling speculation that McCown was their first choice and that they hired Culley last year only because they feared how rejecting the more experienced coach would look.

Just the fact that McCown, who is white, has been able to interview twice for a head-coaching job with a practically nonexistent résumé speaks to what Black coaches are up against in the NFL. Maybe Culley wasn’t the right long-term fit for the Texans, but if the Texans used him as a shield to hire the coach they actually wanted, that would be beyond insulting.

Unfortunately, in the NFL Black coaches are expected to perform miracles quickly, and when they don’t, it usually costs them their job. In 2018, the Arizona Cardinals fired Steve Wilks after one season. Like Culley, Wilks took over a team with poor prospects, not least because the Cardinals general manager, Steve Keim, had made a series of questionable draft choices. But Wilks was the one who paid the price.

Culley has been judged far more harshly than the Detroit Lions head coach, Dan Campbell, who is white. The Lions have been a woeful franchise for decades. This season, the team flirted with going winless for the second time in franchise history. Campbell won one fewer game than Culley, but despite the Lions’ 3–13–1 record, the mood around Campbell is optimistic and hopeful. Sports Illustrated recently published a listicle bearing the headline “4 Signs Dan Campbell Is Right Coach for Lions.” It praised him for being brought to tears early in the season when Detroit lost to Minnesota and slipped to 0–5. “It is so refreshing to see a head coach who gets emotional,” the author wrote.

Some optimism is warranted: Under Campbell, the Lions, who lost many close games, have been more competitive than their record suggests. Campbell certainly deserves more time to see if he can turn the Lions around. But many Black coaches in similar positions don’t get the same benefit of the doubt when they can’t show immediate improvements. And sometimes, even when the results are impressive, that’s still not good enough.

The Lions are the same franchise that fired Jim Caldwell in 2017 after he led the Lions to two playoff appearances in his four seasons as head coach. Caldwell, who is Black and went to a Super Bowl as the head coach of the Indianapolis Colts in 2010, had three winning seasons, including his final season, when Detroit was 9–7. The Lions thought they could do better than Caldwell. But they couldn’t. Matt Patricia, the Lions’ next coach, failed to have a winning season, never went to the playoffs, and finished his Lions tenure with a 13–29 record. Caldwell was 36–28.

Meeting a fate similar to Caldwell’s was Flores, who was fired despite guiding the Dolphins to their first back-to-back winning seasons since 2002–03. Some reports ascribed the shocking move to Flores’s conflicts with the general manager, Chris Grier, and the starting quarterback, Tua Tagovailoa. Testy relationships within a football team are nothing new. But plenty of other coaches with strong personalities keep their job, especially after showcasing the kind of promise that Flores exhibited.

Even if Flores lands at another team—he’s rumored to be the top candidate for the New York Giants’ opening—or other Black coaches are named head coaches in the current hiring cycle, his firing and Culley’s have left a unique stain on the NFL’s hiring process for head coaches.

Since its inception, the NFL has twice expanded the reach of the Rooney Rule in an effort to force NFL owners to consider minority candidates more seriously. The rule was well-intentioned, and sometimes over the years it has appeared to have some impact. But no substantive change will occur as long as NFL owners continue to see Black coaches as expendable. These owners’ failure to value Black male leadership becomes obvious at this time every season—just as it did last year. Unfortunately, it’s a serious problem that the NFL doesn’t seem to have the motivation or will to solve.